Mental health and physical health are fundamentally linked. People living with a serious mental illness are at higher risk of experiencing a wide range of chronic physical conditions. Conversely, people living with chronic physical health conditions experience depression and anxiety at twice the rate of the general population. (December, 2008)

Introduction

Mental health and physical health are fundamentally linked. People living with a serious mental illness are at higher risk of experiencing a wide range of chronic physical conditions. Conversely, people living with chronic physical health conditions experience depression and anxiety at twice the rate of the general population. Co-existing mental and physical conditions can diminish quality of life and lead to longer illness duration and worse health outcomes.1 This situation also generates economic costs to society due to lost work productivity and increased health service use.

Understanding the links between mind and body is the first step in developing strategies to reduce the incidence of co-existing conditions and support those already living with mental illnesses and chronic physical conditions.

Why do mental illnesses and chronic physical conditions co-exist?

Both mind and body are affected by changes to physiological and emotional processes, as well as by social factors such as income and housing. These three pathways of biology, illness experience, and the social determinants of health can increase the likelihood of someone living with a mental illness or chronic physical condition developing a co-existing condition.

People living with mental illnesses experience a range of physical symptoms that result both from the illness itself and as a consequence of treatment. Mental illnesses can alter hormonal balances and sleep cycles, while many psychiatric medications have side-effects ranging from weight gain to irregular heart rhythms.2,3 These symptoms create an increased vulnerability to a range of physical conditions.

Furthermore, the way that people experience their mental illnesses can increase their susceptibility of developing poor physical health. Mental illness can impact social and cognitive function and decrease energy levels, which can negatively impact the adoption of healthy behaviours. People may lack motivation to take care of their health. Or, they may adopt unhealthy eating and sleeping habits, smoke or abuse substances, as a consequence or response to their symptoms, contributing to worse health outcomes.

Stats and Facts

- Canadians who report symptoms of depression also report experiencing three times as many chronic physical conditions as the general population. Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2008

- Canadians with chronic physical conditions have twice the likelihood of also experiencing a mood or anxiety disorder when compared to those without a chronic physical condition. Government of Canada, 2006

- One out of every two Canadians with major depression and a co-existing chronic physical condition report limitations in their day-to-day activities. S. Patten, 1999

People living with mental illnesses often face higher rates of poverty, unemployment, lack of stable housing, and social isolation. These social factors increase the vulnerability of developing chronic physical conditions. For example, people who are unable to afford healthier food options often experience nutritional deficiencies. Poor nutrition is a significant risk factor for the development of heart disease and diabetes. Similarly, it is more difficult to be physically active when living in an unsafe or unhealthy neighbourhood.

Some chronic physical conditions can cause high blood sugar levels and disrupt the circulation of blood, which can impact brain function.4 People living with chronic physical conditions often experience emotional stress and chronic pain, which are both associated with the development of depression and anxiety. Experiences with disability can also cause distress and isolate people from social supports. There is some evidence that the more symptomatic the chronic physical condition, the more likely that a person will also experience mental health problems.5 Thus, it is not surprising that people with chronic physical conditions often self-report poor mental health.6

Mental and physical illnesses also share many symptoms, such as food cravings and decreased energy levels, which can increase food consumption, decrease physical activity and contribute to weight gain. These factors increase the risk of developing chronic physical conditions and can also have a detrimental impact upon an individual’s mental well-being.

The social determinants of health can also impact upon a person’s mental well-being. People living in poverty with chronic physical conditions are at risk of developing mental health problems and may face barriers to accessing mental health care, contributing to worsening mental health problems. Housing insecurity can be particularly stressful and lead to poorer mental and physical health.

Common co-existing mental illnesses and chronic physical conditions

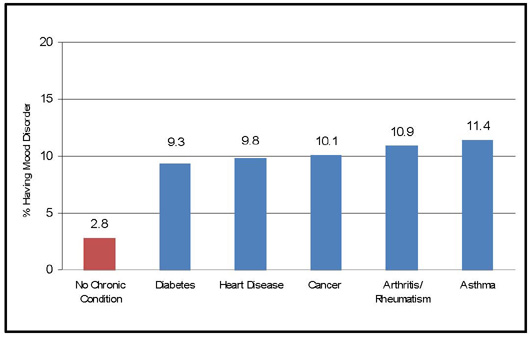

People living with the most common chronic physical conditions in Ontario also face worse mental health than the general population. Figure 1 illustrates the elevated rates of mood disorders in Ontarians with diabetes, heart disease, cancer, arthritis and asthma.

People with serious mental illnesses face a greater risk of developing a range of chronic physical conditions compared to the general population, impacting almost every biological system in the body.7 Table 1 summarizes the risk of people with a mental illness developing various chronic physical conditions. Higher rates of diabetes, heart disease and respiratory conditions in people with serious mental illnesses have been well-established by the research; the links to cancer are still emerging and preliminary findings vary depending on type of cancer.

Diabetes

Diabetes rates are significantly elevated among people with mental illnesses.8 Both depression and schizophrenia are risk factors for the development of type 2 diabetes due to their impact on the body’s resistance to insulin.9,10 People with mental illnesses also experience many of the other risk factors for diabetes, such as obesity and high cholesterol levels. Antipsychotic medications have been shown to significantly impact weight gain; obesity rates are up to 3.5 times higher in people with serious mental illnesses in comparison to the general population.11

Conversely, people with diabetes have nearly twice the rate of diagnosed mental illnesses as those without diabetes. Forty percent of people with diabetes12 also exhibit elevated symptoms of anxiety.13 People living with diabetes often experience significant emotional stress which can negatively affect an individual’s mental health. The biological impact of high blood sugar levels is also associated with the development of depression in people with diabetes. Left untreated, co-existing diabetes, poor mental health and mental illnesses can hinder self-care practices and increase blood sugar levels, contributing to worsening mental and physical health.

Heart Disease and Stroke

People with serious mental illnesses often experience high blood pressure and elevated levels of stress hormones and adrenaline which increase the heart rate. Antipsychotic medication has also been linked with the development of an abnormal heart rhythm. These physical changes interfere with cardiovascular function and significantly elevate the risk of developing heart disease among people with mental illnesses.14 Similarly, people with serious mental illnesses also experience higher rates of many other risk factors for heart disease, such as poor nutrition, lack of access to preventive health screenings, and obesity. In Canada, women with depression are 80 percent more likely to experience heart disease than women without depression.15 This is attributed to both biological and social factors. Similarly, people with mental illnesses have up to a three times greater likelihood of having a stroke.16

Conversely, there are significantly elevated rates of depression among people with heart disease. It is three times more likely that a person with heart disease will experience depression when compared to people who do not have heart problems.17 Depression also often occurs following a stroke.18

Co-existing heart disease and mental illness contribute to worse health status and higher health care utilization rates.19 Similarly, psychological distress has been shown to slow rehabilitation from stroke and increase the risk of stroke-related death.20

Figure 1. Comparison of Mood Disorder Rates in Ontarians with and without Chronic Physical Conditions

Table 1. Risk of People with a Mental Illness Developing Specified Chronic Physical Conditions

| Chronic Physical Condition | Relative Risk (RR) or Odds Ratio (OR) or Standardized Incidence Ratio (SIR) | Type of Study and Source |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | RR = 1.6 for people with depression | Meta-analysis B. Mezuk, W.W. Eaton, S. Albrecht and S. Hill Golden, “Depression and Type 2 Diabetes over the Lifespan,” Diabetes Care 31, no. 12 (2008): 2383-2390. |

| Heart Disease | RR = 1.6 for people with depression | Meta-analysis R. Rugulies, “Depression as a Predictor for Coronary Heart Disease: A Review and Meta-Analysis,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 23 no. 1 (2002): 51-61. |

| Stroke | RR = 3.1 for people with depression | Prospective study S.L. Larson, P.L. Owens, D. Ford and W. Eaton, “Depressive Disorder, Dysthymia, and Risk of Stroke: Thirteen-Year Follow-Up from the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study,” Stroke: Journal of the American Heart Association 32, no. 9 (2001): 1979-1983. |

| COPD | OR = 3.8 – 5.7 for people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder | Cross-sectional study S. Himelhoch et al., “Prevalence of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease among Those with Serious Mental Illness,” American Journal of Psychiatry 161, no. 12 (2004): 2317-2319. |

| Breast Cancer | OR = 1.5 for people with schizophrenia | Retrospective Study J. Hippisley-Cox, Y. Vinogradova, and C. Coupland, “Risk of Malignancy in Patients with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder,”Archives of General Psychiatry 64 no. 12 (2007): 1368-1376. |

| SIR = 1.2 for people with schizophrenia | Retrospective study D. Lichtermann et al., “Incidence of Cancer among Persons with Schizophrenia and Their Relatives,” Archives of General Psychiatry48, no. 6 (2001): 573-578. |

|

| Colon Cancer | OR = 2.9 for people with schizophrenia | Retrospective Study (Hippisley-Cox et al., 2007) |

| SIR = 0.9 for people with schizophrenia | Retrospective study (Lichtermann et al., 2001) |

|

| Lung Cancer | OR = 0.59 for people with schizophrenia | Retrospective Study (Hippisley-Cox et al., 2007) |

| SIR = 2.2 for people with schizophrenia | Retrospective study (Lichtermann et al., 2001) |

Respiratory Conditions

People with serious mental illnesses have a significantly increased likelihood of developing a range of chronic respiratory conditions including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic bronchitis and asthma.21,22 Smoking is commonly identified as a risk factor for respiratory illnesses. People with mental illnesses have high smoking rates, due in part to historical acceptability of smoking in psychiatric institutions, the impact of nicotine on symptom control, and the positive social aspects of smoking. Social factors such as poverty, unstable housing, unemployment and social exclusion may also impact upon both smoking rates and the development of respiratory conditions, but there has been little research on this topic among people with serious mental illnesses.

People living with chronic respiratory diseases experience significantly elevated rates of anxiety and depression. Almost three out of every four people with severe COPD also experience anxiety and/or depression.23 A co-existing mental health problem can lead to poor self-care practices which can increase the symptoms of COPD and contribute to increased hospital admissions, health care costs, and reduced quality of life. People who experience asthma attacks similarly have a greater likelihood of experiencing anxiety and panic disorders.24 This is thought to be related to the life-threatening possibility of a severe asthma attack. In addition, some asthma medications have been demonstrated to alter mood.

Cancers

The research linking mental illness and cancer has yielded mixed results. Recent research has found significantly higher rates of cancer among people with schizophrenia than expected.25 People with schizophrenia have been found in some studies to have approximately twice the risk of developing gallbladder and bowel cancers, which may be linked to high-fat diets.26,27 Findings are inconclusive for respiratory cancers. Many studies have found decreased rates of respiratory cancers among people with serious mental illnesses; it has been suggested that this lower risk may be linked with past institutionalization which may have protected people from environmental risks.28 A contradictory study has recently found twice the risk of developing cancers of the lungs and the pharynx, and suggests this may be linked to increased smoking rates.29

People living with cancers face a higher risk of developing depression, due in part to high levels of stress, emotional upset, and changes in body image.30 A co-existing mental health problem can interfere with cancer treatment and remission. For example, older women with breast cancer and a diagnosis of depression were significantly less likely to receive optimal treatment.31

Arthritis

Research has consistently found a lower rate of arthritis in people with serious mental illnesses than the general population. It has been previously suggested that schizophrenia may reduce the risk of developing arthritis due to genetics, the anti-inflammatory side effects of antipsychotic medications, and more sedentary lifestyles linked to institutionalization and illness. However, it has been argued that rates of arthritis may in fact be underreported in people with serious mental illnesses due to a reduced likelihood of reporting pain.32 A recent study of health insurance data in the United States supports this theory; the study found significantly higher odds of developing arthritis among people with schizophrenia than the general population.33

By comparison, people with arthritis are at significantly elevated risk of developing mood and anxiety disorders.34 These rates are strongest among younger age groups and are also linked to experiences with frequent or chronic pain.

Addressing Access to Health Care

People with serious mental illnesses face many barriers to accessing primary health care. These barriers are complex and range from the impact of poverty on the ability to afford transportation for medical appointments to systemic barriers related to the way that primary health care is currently provided in Ontario. For example, people with mental illnesses who live in precarious housing may not have an OHIP card due to the lack of a permanent address or a safe place to store identification. Some physicians may also be reluctant to take on new patients with complex needs or psychiatric diagnoses, due to short appointment times or lack of support from mental health specialists.35 Consequently, access to primary health care has rated as a top unmet need for people with mental illnesses.36

The stigma associated with mental illness also continues to be a barrier to the diagnosis and treatment of chronic physical conditions in people with mental illnesses. Stigma acts as a barrier in multiple ways. It can directly prevent people from accessing health care services, and negative past experiences can prevent people from seeking health care out of fear of discrimination. Furthermore, stigma can lead to a misdiagnosis of physical ailments as psychologically based. This “diagnostic overshadowing” occurs frequently and can result in serious physical symptoms being either ignored or downplayed.37 Consumers have argued that even if physical symptoms such as pain are manifestations of psychological distress, people should still be treated for their physical complaints.38

People with serious mental illnesses who have access to primary health care are less likely to receive preventive health checks. They also have decreased access to specialist care and lower rates of surgical treatments following diagnosis of a chronic physical condition.39

The mental health of people with chronic physical conditions is also frequently overlooked. Diagnostic overshadowing can mask psychiatric complaints, particularly for the development of mild to moderate mental illnesses. Short appointment times are often not sufficient to discuss mental or emotional health for people with complex chronic health needs.40 Finally, mental illnesses and chronic physical conditions share many symptoms, such as fatigue, which can prevent recognition of co-existing conditions.

There are several initiatives in Ontario that can help to reduce barriers to health care. The Chronic Disease Prevention and Management Framework being implemented in Ontario has the potential to address the importance of emotional and mental health care for people living with a chronic physical condition. Collaborative mental health care initiatives such as shared care approaches are linking family physicians with mental health specialists and psychiatrists to provide support to primary health care providers serving people with mental illnesses and poor mental health.

Some community mental health agencies have established primary health care programs to ensure their clients with serious mental illnesses are receiving preventive health care and assistance in managing co-existing chronic physical conditions.

However, these initiatives currently lack sufficient infrastructure, incentives and momentum. For example, only half of Ontario’s doctors reported that they coordinate, collaborate or integrate the health care they provide with psychiatrists, mental health nurses, counsellors, or social workers.41 This rate may improve as Family Health Teams begin to provide collaborative care with non-physician mental health specialists as part of Ontario’s primary health care reform.

Current Activities

CMHA Ontario is active in supporting people to promote their mental and physical health. We do this by advocating for increased access to primary health care, as well as for more affordable housing, income and employment supports, and for healthy public policies that address the broad determinants of health.

We have released two papers, “What Is the Fit between Mental Health, Mental Illness and Ontario’s Approach to Chronic Disease Prevention and Management?” and “Recommendations for Preventing and Managing Co-Existing Chronic Physical Conditions and Mental Illnesses,” that raise issues and provide recommendations to improve the prevention and management of co-existing mental illnesses and chronic physical conditions. The recommendations address the prevention and management of mental health problems in people with chronic physical conditions, and the prevention and management of chronic physical conditions in people with serious mental illnesses.

We have also launched the Minding Our Bodies initiative in partnership with YMCA Ontario and York University’s Faculty of Health, with support from the Ontario Ministry of Health Promotion through the Communities in Action Fund, designed to increase capacity within the community mental health system in Ontario to promote active living and to create new opportunities for physical activity for people with serious mental illness.

References

- S.B. Patten, “Long-Term Medical Conditions and Major Depression in the Canadian Population,” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 44 no. 2 (1999): 151-157.

- D.L. Evans et al., “Mood Disorders in the Medically Ill: Scientific Review and Recommendations,” Biological Psychiatry 58, no. 3 (2005): 175-189.

- S. Leucht et al., “Physical Illness and Schizophrenia: A Review of the Literature,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 116, no. 5 (2007): 317-333.

- D.L. Evans et al., “Mood Disorders in the Medically Ill: Scientific Review and Recommendations,” Biological Psychiatry 58, no. 3 (2005): 175-189.

World Federation for Mental Health, “The Relationship between Physical and Mental Health: Co-occurring Disorders” (World Mental Health Day, 2004), www.wfmh.org.

Government of Canada, The Human Face of Mental Health and Mental Illness in Canada, Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada (Catalogue No. HP5-19/2006E, 2006). - C.P. Carney, L. Jones and R.F. Woolson, “Medical Comorbidity in Women and Men with Schizophrenia: A Population-Based Controlled Study,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 21 no. 11 (2006): 1133-1137.

- J.P. McEvoy et al., “Prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome in Patients with Schizophrenia: Baseline Results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Schizophrenia Trial and Comparison with National Estimates from NHANES III,” Schizophrenia Research 80, no. 1 (2005): 19-32.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information, A Framework for Health Outcomes Analysis: Diabetes and Depression Case Studies (Ottawa: CIHI, 2008).

- L. Dixon et al., “Prevalence and Correlates of Diabetes in National Schizophrenia Samples,” Schizophrenia Bulletin 26 no. 4 (2000): 903-912.

- S. Coodin, “Body Mass Index in Persons with Schizophrenia,” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 46 no. 6 (2001): 549-555.

- L.C. Brown, L.W. Svenson, and C.A. Beck, “Diabetes and Mental Health Disorders in Alberta,” in Alberta Diabetes Atlas 2007 (Institute of Health Economics, 2007), 113-125.

- A.B. Grigsby et al., “Prevalence of Anxiety in Adults with Diabetes: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 53, no. 6 (2002): 1053-1060.

- D.C. Goff et al., “A Comparison of Ten-Year Cardiac Risk Estimates in Schizophrenia Patients from the CATIE Study and Matched Controls,” Schizophrenia Research 80, no. 1 (2005): 45-53.

- H. Gilmour, “Depression and Risk of Heart Disease,” Health Reports, 19, no. 3 (July 2008), Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 82-003-XPE, www.statcan.ca.

- S.L. Larson, P.L. Owens, D. Ford and W. Eaton, “Depressive Disorder, Dysthymia, and Risk of Stroke: Thirteen-Year Follow-Up from the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study,” Stroke: Journal of the American Heart Association 32, no. 9 (2001): 1979-1983.

- H. Johansen, “Living with Heart Disease – The Working-Age Population,” Health Reports, 10, no. 4 (Spring 1999): 33-45, Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 82-003, www.statcan.gc.ca.

- M. L. Hackett and C. S. Anderson, “Predictors of Depression after Stroke: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies,” Stroke 36, no. 10 (2005): 2296-2301.

- P.A. Kurdyak et al., “The Relationship between Depressive Symptoms, Health Service Consumption, and Prognosis after Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Prospective Cohort Study,” BMC Health Services Research 8: 200 (published online September 30, 2008), www.biomedcentral.com.

- M. May et al., “Does Psychological Distress Predict the Risk of Ischemic Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack? The Caerphilly Study,” Stroke 33, no. 1 (2002): 7-12.

- S. Himelhoch et al., “Prevalence of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease among Those with Serious Mental Illness,” American Journal of Psychiatry 161, no. 12 (2004): 2317-2319.

- R.S. McIntyre et al., “Medical Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder: Implications for Functional Outcomes and Health Service Utilization,” Psychiatric Services 57, no. 8 (2006): 1140-1144.

- J. Maurer et al., “Anxiety and Depression in COPD: Current Understanding, Unanswered Questions, and Research Needs,” Chest 134, no. 4, supplement (2008): 43S-56S.

- R.D. Goodwin, F. Jacobi and W. Thefeld. “Mental Disorders and Asthma in the Community,” Archives of General Psychiatry 60 no. 11 (2003): 1125-1130.

- D. Lichtermann et al., “Incidence of Cancer among Persons with Schizophrenia and Their Relatives,” Archives of General Psychiatry 48, no. 6 (2001): 573-578.

- D. Lichtermann et al., “Incidence of Cancer among Persons with Schizophrenia and Their Relatives,” Archives of General Psychiatry 48, no. 6 (2001): 573-578.

- Disability Rights Commission [UK], Equal Treatment: Closing the Gap — A Formal Investigation into Physical Health Inequalities Experienced by People with Learning Disabilities and/or Mental Health Problems (2006), 83.137.212.42.

- J. Hippisley-Cox, Y. Vinogradova, C. Coupland, and C. Parker. “Risk of Malignancy in Patients with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder,” Archives of General Psychiatry 64 no. 12 (2007): 1368-1376.

- D. Lichtermann, et al. “Incidence of Cancer among Persons with Schizophrenia and their Relatives,” Archives of General Psychiatry 48 no. 6 (2001):573-578.

- World Federation for Mental Health, “The Relationship between Physical and Mental Health: Co-occurring Disorders,” (World Mental Health Day, 2004), www.wfmh.org.

- J.S. Goodwin, D.D. Zhang, and G.V. Ostir, “Effect of Depression on Diagnosis, Treatment, and Survival of Older Women with Breast Cancer,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52, no. 1 (2004): 106-111.

- S. Leucht et al., “Physical Illness and Schizophrenia: A Review of the Literature,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 116, no. 5 (2007): 317-333.

- C.P. Carney, L. Jones and R.F. Woolson, “Medical Comorbidity in Women and Men with Schizophrenia: A Population-Based Controlled Study,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 21, no. 11 (2006): 1133-1137.

- S.B. Patten, J.V.A. Williams and J.L. Wang, “Mental Disorders in a Population Sample with Musculoskeletal Disorders,” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 7, no. 37 (2006), www.biomedcentral.com.

- M.A. Kasperski, “Collaborative Mental Health Care Network Interim Report Year II: 2002-2003,” Ontario College of Family Physicians, (February 20, 2003).

- M. Bédard, C. Gibbons and S. Dubois, “The Needs of Rural and Urban Young, Middle-Aged, and Older Adults with a Serious Mental Illness,” Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine 12 no 3 (2007):167-175.

- Disability Rights Commission [UK], Equal Treatment: Closing the Gap — A Formal Investigation into Physical Health Inequalities Experienced by People with Learning Disabilities and/or Mental Health Problems (2006), 83.137.212.42.

- Highland Users Group, Mental Health and Physical Health: The Views of HUG on the Relationship between Physical and Mental Health and What Can Keep Us Healthy (June 2008), www.iimhl.com.

- S. Kisely et al., “Inequitable Access for Mentally Ill Patients to Some Medically Necessary Procedures,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 176, no. 6 (2007): 779-784.

- M.A. Craven, M. Cohen, D. Campbell, J. Williams, and N. Kates, “Mental Health Practices of Ontario Family Physicians: A Study Using Qualitative Methodology” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42 (November 1997): 943-949.

- National Physician Survey, “2007 Results: Ontario Results by FP/GP or Other Specialist, Sex, Age, and All Physicians,” www.nationalphysiciansurvey.ca.