This discussion paper explores the relationship between chronic disease, mental illness and mental health. It is intended to initiate dialogue about the issues and opportunities inherent in Ontario’s shift towards improved chronic disease prevention and management, and to be a foundation for consultations and discussions with people with mental illnesses, their families, health care providers and other stakeholders. (August, 2008)

Preamble

As Ontario begins to reorient the health system to respond to the increasing prevalence and burden of chronic conditions, Canadian Mental Health Association, Ontario believes it is timely and essential to initiate dialogue on the fit between mental health, mental illness and Ontario’s approach to chronic disease prevention and management. The chronic disease prevention and management (CDPM) framework, developed by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care in collaboration with the Ministry of Health Promotion, has been broadly disseminated and is in the initial stages of implementation in this province.

Serious mental illnesses are not preventable in the same way as chronic physical conditions, but there are strategies known to promote mental health and reduce the risk of mental illnesses. It is possible that serious mental illnesses may benefit from a CDPM approach, but there is little available research and writing on this topic. Consideration must also be given to whether the recovery approach, as well as the services and supports that are already in place to support people with serious mental illnesses, fit within a CDPM framework.

One of the strengths of the CDPM approach is its potential for integrating physical and mental health care. This is particularly of value in improving the physical health care of people with serious mental illnesses, a population whose physical health is often poor and who are at high risk of developing diabetes and heart disease. In addition, there has been considerable research on addressing depression as a chronic condition. People with chronic physical conditions are at risk of depression, and the CDPM model appears to have the potential to improve screening and management of depression in people with chronic physical conditions.

CMHA Ontario has prepared two papers on the relationship between chronic disease, mental illness and mental health. The first is this discussion paper, “What Is the Fit Between Mental Health, Mental Illness and Ontario’s Approach to Chronic Disease Prevention and Management?” Its purpose is to initiate dialogue about the issues and opportunities inherent in Ontario’s shift towards improved chronic disease prevention and management. The paper is intended to be a foundation for consultations and discussions with people with mental illnesses, their families, health care providers and other stakeholders.

While further discussion is clearly needed, the health system has already begun to move towards improving the management of chronic physical conditions through a CDPM approach. CMHA Ontario believes it is important that action begin immediately to address co-existing chronic physical conditions and mental illnesses, and there is clear evidence to support some health system changes that would begin to do so. For this reason, we have prepared a second paper, “Recommendations for Preventing and Managing Co-Existing Chronic Physical Conditions and Mental Illnesses.” The five-page document presents a very short summary of the issues related to co-existing conditions described in our discussion paper and outlines 13 recommendations for change.

We look forward to participating with others in advancing health system thinking and action regarding the opportunities to address mental health and mental illnesses within chronic disease prevention and management. Please join us in this dialogue.

1.0 Introduction

Health systems are in transition. Canada and other countries are shifting from a structure built primarily for acute care to a more responsive health system appropriately designed for the prevention and management of chronic conditions. The place of mental health and mental illnesses within a chronic disease strategy is not yet clear. There are associations between chronic physical conditions, mental health and mental illnesses that make this a cogent issue. Poor mental health is a risk factor for developing chronic physical conditions, people with chronic physical conditions are at risk of developing mental health problems, and people with serious mental illnesses frequently have co-existing chronic physical conditions. Mental illnesses can themselves be perceived as chronic illnesses.

The place of mental illnesses and mental health within the chronic disease prevention and management (CDPM) framework in Ontario has yet to be well-defined. Canadian Mental Health Association, Ontario (CMHA Ontario) seeks to clarify the issues and explore opportunities for promoting mental health, supporting people with mental illnesses, and addressing the prevention and management of co-existing mental illnesses and chronic physical conditions.

2.0 The Current Context

Improving chronic disease prevention and management is a priority in Ontario’s current health care agenda. The CDPM framework,1 developed by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) in collaboration with the Ministry of Health Promotion, has been widely disseminated across the health system. An implementation strategy, beginning with diabetes prevention and management,2 is currently being developed.

The CDPM framework requires a reorientation of the health system. It will impact multiple elements of the provincial government’s transformation agenda for the health system, including Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs), primary health care, public health, e-health, health human resource strategies and strategies for specific chronic conditions.3 It is expected that the upcoming implementation of the diabetes strategy will initiate the health system reorientation necessary to proceed.

The 14 LHINs have been tasked by the MOHLTC with taking action on chronic disease prevention and management. Many LHINs refer to chronic disease prevention and management in their integrated health service plans, while others have yet to make clear what they will do. Family health teams are also being encouraged to integrate chronic disease prevention and management into their practices.4 Indeed, primary health care has a central role in the implementation of CDPM.

As the health system is reoriented for chronic disease prevention and management, it will be important for policy-makers and service providers to consider and take action on appropriate opportunities to address mental health and mental illnesses within the CDPM framework.

3.0 Ontario’s Chronic Disease Prevention and Management Framework

The MOHLTC chronic disease prevention and management framework evolved out of the original chronic care model developed in 1996 by the MacColl Institute for Healthcare Innovation in the United States. Evidence was accumulating that clinical practices designed to treat acute illness were not resulting in effective outcomes for patients with chronic conditions. The MacColl Institute recommended that: health care providers utilize evidence as a tool for decision-support to guide clinical care, multidisciplinary teams be created to provide the full range of health services needed, information systems be developed to organize planned visits and protocols for treatment, and education and support be offered to patients, in order for them to actively participate in the management of their chronic conditions.5

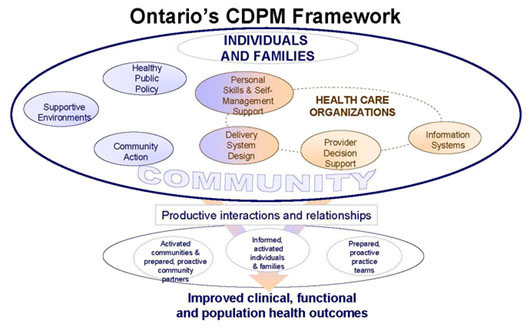

Ontario’s Chronic Disease Prevention and Management Framework6

In 2003, British Columbia developed the Expanded Chronic Care Model, which incorporates prevention and health promotion into the original model.7 The Ontario framework is a modification of the British Columbia approach.

In the Ontario CDPM framework,8 health care organizations continue to be recognized as an important but not exclusive component of addressing chronic conditions. The framework envisions health care organizations working together and with other community organizations, using evidence and other information tools, to provide comprehensive, well-coordinated services and to enable patients to be active in their own self-care.

The framework identifies health promotion and prevention as integral strategies for addressing chronic conditions — at both the individual and population level. Governments assume an explicit responsibility for health through policies that address social, economic and physical factors that impact the ability of people to lead healthy lives. Active communities work in collaboration with individuals, families and health care organizations to create the social conditions for good health and improve the health of individuals. Healthy public policies, community action and supportive environments reduce both the burden and the incidence of chronic conditions.

Thus, in the CDPM framework, health care providers, individuals and families, and communities all have a role in promoting health and preventing chronic conditions, as well as achieving successful health outcomes for people with chronic conditions.

4.0 Mental Illnesses as “Chronic Diseases”

One in five Canadians will experience a mental illness in their lifetime.9For many, this will be experienced as an episode, not of long-term duration. However, four of the 10 leading causes of disability worldwide are mental disorders. Depression is the leading cause of disability as measured by years lost to disability and the fourth leading contributor to the global burden of disease.10 The lifetime prevalence of depression in Canada is 12.2 percent11.

In its research to support the development of the chronic disease framework, the MOHLTC calculated depression as one of the top 10 chronic conditions in terms of disease burden and economic cost in Ontario.12 Recognizing the impact of depression on Ontarians, the MOHLTC convened a group of stakeholders to work with ministry staff to develop a depression strategy that was completed in 2007 and is now awaiting approval. The depression strategy was developed independent of the chronic disease strategy. It is not yet clear whether it will be integrated with the MOHLTC’s chronic disease strategy.

Health policies in most countries and most Canadian provinces address serious mental illnesses separately from chronic physical conditions. To date, Ontario has done the same. Ontario has a policy framework for people with serious mental illnesses, “Making It Happen,”13 that is still in the process of being implemented.

While the chronic disease literature includes serious mental illnesses as chronic conditions, the literature on mental illnesses does not. In the latter, serious mental illnesses are not framed in terms of chronicity or illness management but around the concept of recovery.

Recovery is about people and how they overcome the impacts of a mental illness. [People living with a mental illness] describe it in different ways, but common to most accounts is regaining a significant degree of control in one’s life and finding a positive sense of self and a meaningful place in the world. The illness loses its central and life-defining position and takes on a more secondary role. Although recovery is a deeply personal process, it is one that must always be seen in a complex social context. Recovery’s partners — excellent services and supports, a positive way of understanding and making sense of illness, and the personal base of strength and resilience needed to cope successfully — are an integral part of the picture.14

5.0 Chronic Disease Prevention and Mental Illnesses

Serious mental illnesses are not preventable chronic conditions in the same way as the chronic physical conditions that are the focus of prevention efforts in Ontario.15 There are, however, a wide range of policy and program approaches that have been shown to reduce risk factors, strengthen protective factors, reduce symptoms of mental illnesses, decrease disability and prevent the onset of some mental health problems. The move towards embracing an integrated chronic disease prevention and management approach in the health system provides several opportunities for addressing mental illnesses.

Individual lifestyle changes alone cannot prevent mental illnesses.

Chronic physical conditions and mental illnesses share many of the same risk and protective factors rooted in the biological, behavioural and broad determinants of health. Risk and protective factors combine to have a strong interactive effect, and exposure to multiple risk factors over time has a cumulative effect. Prevention of physical and mental illnesses must involve multi-faceted approaches that address complex interactions between various factors. However, the disease burden of chronic physical conditions can be significantly reduced by addressing three individual behaviours: tobacco smoking, unhealthy diet and physical inactivity. A primary focus of chronic disease prevention is improving healthy behaviours.16, 17 Although making healthy choices can have an impact on one’s mental health, there is little evidence that a focus on healthy behaviours alone would have a significant effect on the incidence or prevalence of serious mental illnesses.

Interventions at the population level can reduce risk factors for mental illnesses.

The CDPM framework recognizes the importance of community action, supportive environments and public policies to support health. Action on these multiple levels can promote both physical and mental health by moving beyond a narrow focus on individual lifestyle to a broader focus on addressing the determinants of population health in this province. There is a growing recognition in the field of chronic disease prevention of the importance of population health interventions in the prevention of chronic physical conditions.18, 19

The broad determinants of health, such as income, housing, education, employment and social inclusion, have been shown to be protective of mental health. Conversely, populations lacking these elements are at increased risk of mental illnesses. However, unlike the lifestyle factors for chronic physical conditions, the strength of the association between any single risk factor and poor mental health is not as strong or straightforward.

Most of the risk factors for mental disorders, in and of themselves, have a very low likelihood of actually causing a disorder… However, if a large population of individuals is exposed to a weak risk factor, then preventing or interrupting exposure to this factor can result in valuable reductions in the burden of associated disorder.20

Work to increase the protective factors for mental health and to decrease the risk factors for mental illnesses is best achieved at a population level. As the World Health Organization states:

High comorbidity among mental disorders and their interrelatedness with physical illnesses and social problems stress the need for integrated public health policies, targeting clusters of related problems, common determinants, early stages of multi-problem trajectories and populations at multiple risks.21

Creating supportive environments focuses on the impact of our working, built and social environments on physical and mental health. For example, building housing developments with adequate green space can encourage social interaction among neighbours, increasing residents’ sense of belonging, and create an environment conducive to active living.

Community action is about bringing people together to address the issues affecting their health or the health of those around them. Community action builds protective factors for mental health, such as social support and self-esteem. It also provides opportunities to learn about an issue and to gain new skills.

Some examples of community action strategies for mental health are: public participation in a government initiative to improve income policy; a multi-sectoral initiative to prevent violence in the community; and a group of parents organizing a parent-child drop-in to provide structured play for children and education in healthy child development for parents. Community action to promote mental health and reduce the risk of mental illness is most effective when it involves people who are at risk, building on their knowledge of what works and what doesn’t and expanding their ownership of the issue and the solutions.

Healthy public policies promote health and can reduce risk factors for both chronic physical conditions and mental illnesses. For example, policies that increase income for individuals and families living in poverty enable people to purchase nutritious food, live in better quality housing and have the means to participate in social-recreational activities that support both physical activity and a sense of belonging within one’s community.

Reduce the burden of chronic physical conditions in people with serious mental illnesses.

Co-existing mental illnesses and chronic physical conditions result in poorer health outcomes and higher mortality than when either type of condition occurs alone. The CDPM framework offers an opportunity for an integrated approach to prevent people with mental illnesses from developing chronic physical conditions.

People with serious mental illnesses have a greater risk of developing a chronic physical condition than people without mental illnesses. They are two to three times more likely to die from chronic heart disease and stroke than individuals without serious mental illnesses.22 People with schizophrenia23 or depression24 have an increased likelihood of developing diabetes than the general population.

There are a number of factors that contribute to poor physical health outcomes among people with serious mental illnesses. Psychotropic medications can induce weight gain, which increases the risk of developing diabetes.25, 26 Poor nutrition and inadequate housing — often consequences of living in poverty — increase vulnerability to chronic conditions.27 Barriers to access physical health care are also a factor.28

Targeted initiatives to support people with mental illnesses to engage in healthy behaviours can be developed and implemented. These initiatives must recognize and deal with the impact of the illness, medications, poverty and other factors that affect people’s ability to engage in healthy behaviours. Population-based health promotion strategies that address poor housing, lack of employment and low incomes are also necessary to reduce the risk factors for chronic conditions in this population.

Reduce the risk of depression in people with chronic physical conditions.

Depression is common among people with chronic physical conditions and is frequently undiagnosed by health care practitioners dealing with the management of chronic conditions. Depression can undermine motivation for self-care, such as compliance with medications, eating well and exercising. People with chronic physical conditions who are depressed experience poorer physical health than those who are not depressed. Ontario’s CDPM framework can be applied to improve prevention and early identification of depression in people with chronic physical conditions.

Many primary health care providers would benefit from professional education and decision support to assist them in preventing, screening and managing depression. Although there are Canadian guidelines to assist physicians with screening and management of depression, they have not been explicitly linked with the management of chronic conditions. Evidence-based protocols and tools need to be developed and integrated to improve health care providers’ management of chronic physical conditions. Information systems can be expanded to track care and remind providers to routinely screen for depression. Enhanced delivery system design can reorganize how multidisciplinary teams and other community providers work together to integrate prevention of depression initiatives into all elements of care.

Chronic disease self-management programs can also help reduce the risk of depression.29 Groups for people who share a chronic condition can offer social support, improve coping skills and reduce stress, all protective factors for mental health. In addition, the opportunities to take charge of one’s situation as part of a group, and tap one’s own strengths to help others, are significant steps in countering the feelings of helplessness that tend to accompany depression. Linking people with community resources that create supportive environments can also reduce the risk of depression. Finally, population-based efforts to improve the determinants of health can positively impact mental health.

Recognizing that chronic physical conditions often coincide with mental health problems, the British Columbia Ministry of Health recently funded Canadian Mental Health Association, British Columbia Division to provide mental health support to people with chronic physical conditions. The Bounce Back project was launched in June 2008. Bounce Back uses evidence-based therapeutic, educational and self-help strategies to support patients to improve their mood and resilience, leading to better health outcomes and enhanced quality of life.30

In Ontario, the MOHLTC has announced the implementation of a diabetes strategy. It is important that the diabetes strategy incorporate action to address prevention of and early intervention for depression among people with or at risk of diabetes.

6.0 Chronic Disease Management and Mental Illnesses

Services and supports for people with serious mental illnesses must be designed around recovery, not disease management.

The recovery approach to serious mental illness has re-oriented the mental health system from a focus on clinical care to a system based on preventing and restoring all of the losses associated with mental illnesses, an individual’s symptoms being only one dimension. Over several decades, government policy in Ontario has moved away from a focus on clinical care in mental health, towards incorporating mental health within an overall recovery framework that recognizes clinical care as only one part of the picture. In contrast, chronic disease management is based on dealing with illness through clinical care and self-management, and providing links to community resources. It is important that the CDPM framework not be seen as a model for recovery from mental illnesses, but is recognized as having a place within a broader recovery perspective.

The course and impact of serious mental illnesses are different from those of chronic physical conditions. The early onset and episodic nature of serious mental illnesses frequently interrupts education, disrupts employment and can create stresses in relationships. Disempowerment, poverty and social isolation are a common result. Chronic physical conditions generally develop later in life and become more debilitating over time. Thus, the situational factors and consequences of having a serious mental illness require additional strategies that extend beyond the CDPM approach for addressing chronic physical conditions.

Recovery from a serious mental illness involves not only an improvement in mental health, but inclusion in community life and self-determination despite continuing to live with an illness. CMHA describes the framework for support necessary for recovery from serious mental illnesses in terms of three pillars of recovery: community resources, personal resources and an expanded understanding of mental illness itself.

CMHA’s Framework for Support31

As illustrated in the Community Resource Base pillar, services and supports for people with serious mental illnesses must be geared to supporting people to move from the role of patient to the role of citizen, and securing the basic elements of citizenship: a home, a job and friends.

The components of the Personal Resource Base can be seen as the tools people with mental illnesses need to achieve a sense of control in their lives: purpose and meaning in life, a sense of belonging, a positive sense of self and a practical understanding of the illness. A sense of control is a critical element of everyone’s mental health. It is particularly important for recovery from a serious mental illness. Traditionally, people with mental illnesses were seen in terms of illness and deficit. They were expected to be passive recipients of care, incapable of having control of their lives. This perspective ignored the resources people need to thrive. The Personal Resource Base is rooted in a balance between the challenge of the illness and the resources that are needed to deal with it and live a full life.

The Knowledge Resource Base recognizes that the skills, knowledge and support provided by health professionals must be complemented by knowledge about the mental illness and how to live with it that comes from the social sciences, from various cultures and communities, and from the lived experience of consumers and families. Social sciences consider the social factors that affect mental health, such as abuse, poverty and discrimination. The consumer’s own experience provides the story of their life circumstances within which illness developed and is experienced. This knowledge is essential both to a full understanding, and to tailor services and support. Families’ experience of the illness can lead them to be strong advocates for access to education, work and full participation in community life, in addition to clinical care for their loved ones with a mental illness. Customary knowledge is the informal knowledge people receive from others, either in the mainstream culture or from any of Canada’s many cultural communities. Much of this knowledge can be positive, such as the need for meaningful activity in one’s life to support good mental health. This knowledge, however, may also include negative stereotypes about people with mental illnesses. Ultimately, bringing together all these perspectives is necessary to improve the mental health literacy of Ontarians, to enable a more complete understanding of the diversity of perspectives on mental illnesses, to promote social acceptance and inclusion, and to create a more effective and responsive array of services and supports.

In the past, when a person was diagnosed with a serious mental illness, schizophrenia in particular, they were defined by their illness and perceived as chronically disabled with little hope of living a full life. People living with mental illnesses have fought hard to break through this stereotype and continue to fight against it. If mental illnesses are linked to a chronic disease framework, it will be important that the meaning and value of recovery remains clear, and the broader foundations for support that promote recovery remain in place. Thus, the label “chronic” is, at best, nuanced and must not subsume hope of a way forward for people living with serious mental illnesses.

Improve the recognition and treatment of depression.

The Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences has raised concerns about how well depression is detected and treated by primary health care providers. While some surveys have found that approximately 90 percent of depressed Canadians had contact with their family doctor in a one-year period for any reason, the Canadian Community Health Survey found that only half of those who self-identified as having depression had contacted their health care provider for mental health reasons.32 The CDPM framework provides an opportunity to improve the detection, screening, diagnosis and treatment of depression in primary health care settings.

Depression is one of the top 10 chronic conditions in Ontario and it is the most common mental health problem faced by Ontarians. Family physicians are the most commonly contacted health provider by people with mental health needs33 and almost 90 percent of Ontario’s family physicians provide mental health care.34 Hence, improving the recognition and treatment of depression in primary health care settings will have a significant impact on addressing depression.

There is good evidence that screening in primary health care settings improves detection rates for depression. The depression screening guidelines for Ontario recommend primary care screening for depression in high-risk groups, including people who have a past history of depression, other mental health problems or a disabling physical illness.35 Screening without follow-up, however, does not improve outcomes. The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care recommends screening of the adult general population in primary care where follow-up is integrated and there is access to case management and other mental health programs.36

Chronic disease management approaches have been successfully used to improve the management of depression. Critical elements that have been demonstrated to make a difference include:

- evidence-based treatment protocols

- a structured diagnostic assessment and a care plan based on the assessment

- collaborative care involving physicians and other health professionals

- psychiatric consults/visits

- education and support for people to manage their own illness

- a relapse prevention plan

- pro-active follow-up and monitoring

- patient registries

- ongoing training for providers37, 38, 39, 40, 41

While the CDPM framework is limited in its applicability to recovery from serious and persistent mental illnesses, it offers several opportunities for early identification and clinical management of depression and for improving the physical health of people with mental illnesses. The CDPM framework may also offer opportunities to address other serious and persistent mental illnesses, provided individuals have access to primary health care in the first place and their provider is skilled and confident in working with people with serious mental illnesses.

Improve the physical health of people with serious mental illnesses, including the management of chronic physical conditions.

There is a high incidence of diabetes and heart disease in people with serious mental illnesses. The mortality rate due to heart disease and stroke is also greater for this group, compared to individuals without a serious mental illness. Mental health service providers in Ontario have identified a need for assistance in managing chronic physical conditions when working with people with serious mental illnesses.

With its emphasis on multidisciplinary teams and proactive community partners, Ontario’s CDPM framework can lead to the realization of new structures and working relationships that address chronic physical conditions in people with mental illnesses. Guidelines for treatment and tools for screening and monitoring physical health can be incorporated into an integrated approach to the mental and physical health of people with serious mental illnesses.

CDPM’s goal of re-orienting primary care to better manage chronic illnesses has the potential to improve the management of chronic physical conditions in people with mental illnesses. However, people with serious mental illnesses frequently have difficulty accessing primary care. In Ontario, innovative partnerships that effectively link community mental health agencies with family health teams and community health centres are increasing collaboration that is improving access to care. These new models range from integrated co-located teams of providers, to models that incorporate referral with ongoing involvement and communication between providers.

These new integrated approaches are improving episodic physical health care for people with mental illnesses and improving access to mental health care for people using primary care services.42 The implementation of CDPM directions for primary health care, together with these new types of integrated approaches, are an ideal opportunity to significantly improve the management of chronic physical conditions in people with serious mental illnesses.

Supporting community mental health agencies to better respond to clients with chronic physical conditions is also necessary. One such example is the Diabetes Resource for Mental Health Clinicians developed for WOTCH Community Mental Health Services by the London InterCommunity Health Centre in London, Ontario.43 This resource is a training program for mental health professionals to assist them in addressing diabetes.

Other targeted initiatives for people with mental illnesses at risk of or living with chronic physical conditions are needed.

7.0 Address Stigma, Discrimination and Mental Health Literacy

Stigma, discrimination and a lack of understanding of mental illnesses create unique barriers to care that are not addressed in the CDPM model.

In order for the chronic disease management approach to yield successful outcomes, people have to be willing to seek help and to participate in their own self-care. However, the stigma attached to mental illnesses often causes individuals to hesitate before seeking and accepting treatment. Individuals may be reluctant to seek help because of the stigma attached to the label of mental illness.

A lack of understanding of mental illnesses also creates barriers. Improving the mental health literacy of Ontarians can assist people to better recognize conditions of poor mental health and feel more at ease seeking help.44

The judgments, attitudes and behaviours of health care providers toward people with mental illnesses can also be a barrier to care. The health care system must address such fears, attitudes and behaviours. Education and training to reduce stigma and increase understanding of the special needs of people with mental illnesses who are at risk of or living with chronic physical conditions is necessary.

8.0 Summary of Key Issues

Improving the integration of the health care system is a priority goal of health reform in Ontario, and a major focus of the Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs). The CDPM framework has the potential to provide a foundation for coordinating the programs and services of LHIN transfer payment agencies with public health, primary health care and non-health agencies. Some LHINs are including mental illnesses under their CDPM mandate. However, as we have described, there are a number of significant differences between serious mental illnesses and chronic physical conditions that raise questions about the appropriateness of the CDPM model as an integrated model for mental illnesses.

The CDPM framework provides an opportunity to improve care for people with serious mental illnesses, integrating physical and mental health care, and improving depression screening and treatment. Recovery for people with serious mental illnesses involves more than prevention and management. It requires cross-sectoral collaboration beyond the health system to address the broad determinants of health. An integrated approach to mental illnesses must address housing, employment, income, education, discrimination and citizenship.

In exploring the place of mental health and mental illnesses within the chronic disease prevention and management framework in Ontario, this discussion paper has identified many issues and opportunities for promoting mental health, supporting people with mental illnesses, and addressing the prevention and management of co-existing mental illnesses and chronic physical conditions.

It is important for those developing chronic disease strategies across Ontario to recognize that mental illnesses are not the same as chronic physical conditions, in terms of both prevention and management. At the same time, the CDPM framework provides an opportunity to improve the recognition and treatment of depression, the mental health problem that affects the highest proportion of Ontarians. In particular, people with chronic physical conditions are at risk of poorer mental health, especially depression. Similarly, people living with mental illnesses are often living with chronic physical conditions or are at risk of developing them. Care and support for this population can be improved through targeted approaches to prevention, improved access to primary care and enhancing resources for mental health service personnel to support their clients who are experiencing chronic physical conditions.

Individual-level interventions to improve the diet and physical activity of people with mental illnesses, and reduce their use of tobacco, will not be effective in addressing co-existing chronic physical conditions without tackling systemic barriers such as poverty and stigma. Population health interventions that improve the determinants of health will reduce the risk factors for both chronic physical conditions and mental illnesses.

9.0 Conclusions

CMHA Ontario has prepared this paper to generate dialogue and action to promote the mental health of Ontarians and address the needs of individuals with mental illnesses. This is a timely discussion as Ontario’s health system shifts from a focus on acute care to chronic conditions.

Key opportunities include:

Address preventable risk factors for mental illnesses and chronic physical conditions through cross-sectoral collaboration.

- Address the broad determinants of health that are risk factors for both mental illnesses and chronic physical conditions. Specifically, develop healthy public policies that enhance housing, employment and education opportunities, as well as reduce poverty.

- Engage communities in action and create supportive environments with the goal of improving the social environment, which is known to impact physical and mental health.

Incorporate prevention and management strategies to address the existence of depression in people with chronic physical conditions.

- Incorporate routine screening for depression into the protocols for preventing and managing chronic physical conditions.

- Provide professional education to increase the capacity of physicians and nurse practitioners to screen, diagnose and treat depression.

- Engage multidisciplinary primary health care teams and community mental health service providers in an integrated approach to prevent, screen and manage depression in people with chronic physical conditions.

Develop strategies to address chronic physical conditions in people with serious mental illnesses.

- Improve access to primary health care for people with serious mental illnesses.

- Improve screening of people with serious mental illnesses for chronic physical conditions.

- Develop approaches to support healthy behaviours and self-management of chronic conditions that recognize the particular barriers facing people with serious mental illnesses.

- Improve the capacity of health care providers in physical health care to work with people with serious mental illnesses.

- Provide education and training to reduce stigma, based on best practices in stigma reduction.

- Provide training in the special needs of people with co-existing physical and mental health conditions.

- Improve the capacity of the mental health sector to support people with mental illnesses to prevent and manage chronic physical health conditions.

- Provide education about chronic physical conditions and the links with serious mental illnesses.

- Provide training in prevention and management strategies that are known to be effective with this population.

- Incorporate chronic disease prevention and management approaches into the work of mental health organizations.

Improve delivery system design to foster collaboration between primary health care and community mental health agencies.

- Provide service agreements with clear delineation of roles.

- Ensure shared information technology and protocols for sharing information.

- Support a variety of models of partnership, including co-location, fully integrated teams, inclusion of community mental health agency staff in primary care teams, and inclusion of primary care staff in mental health agencies.

Improve the prevention, detection and treatment of depression in Ontario.

- Include depression prevention, screening and treatment in the chronic disease prevention and management strategy for Ontario.

- Increase training and education of primary care practitioners in screening and treatment protocols for depression.

- Implement the MOHLTC depression strategy.

Recognize that serious and persistent mental illnesses require a unique approach.

- Work cross-sectorally to ensure that people with mental illnesses can not only manage their illness but can make a full recovery to citizenship with adequate housing, employment and inclusion in the community.

10.0 Questions for Discussion

In addition, CMHA Ontario wishes to explore the following issues further with policy-makers and decision-makers in the health system and beyond.

- What opportunities exist for those working on chronic disease prevention and the mental health sector to work together in developing healthy public policy, creating supportive environments and enabling community action?

- Public health plays a significant role in the prevention of chronic physical conditions. What is the potential role for public health in terms of mental health, mental illnesses and chronic disease prevention?

- The development of chronic physical illnesses is a significant issue facing a high percentage of people with serious mental illnesses, yet the population of people with serious mental illnesses is small in comparison to the magnitude of people at risk of chronic physical conditions. How can we ensure that the unique needs of people with serious mental illnesses and co-occurring chronic physical conditions are adequately addressed as the CDPM framework is being implemented?

- What roles do community mental health agencies envision for themselves, given current opportunities in chronic disease prevention and management?

- Based on government policy directions, people with serious and persistent mental illnesses are the first priority for Ontario’s community mental health sector. As a result, gaps in services exist to address the needs of Ontarians with moderate mental illnesses or situational mental health needs. What opportunities might there be to address this gap through the CDPM framework?

- Is the recovery approach to mental illness useful to apply in some capacity to chronic physical conditions?

References

- Marjorie Keast, “Ontario’s Chronic Disease Prevention and Management Framework,” presentation at the Ontario Health Providers Alliance chronic disease prevention and management policy forum (Toronto: April 18, 2007).

- Ontario, “Backgrounder: Diabetes Strategy,” Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and Ministry of Health Promotion (July 22, 2008),www.health.gov.on.ca.

- Keast, “Ontario’s Chronic Disease Prevention and Management Framework.”

- Ontario, “Guide to Chronic Disease Management and Prevention,” Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (September 27, 2005), p. 3,www.health.gov.on.ca.

- Edward H. Wagner, Brian T. Austin and Michael Von Korff, “Organizing Care for Patients with Chronic Illness,” The Milbank Quarterly 74, no. 4 (1996): 511-543.

- Keast, “Ontario’s Chronic Disease Prevention and Management Framework.”

- Victoria J. Barr et al., “The Expanded Chronic Care Model: An Integration of Concepts and Strategies from Population Health Promotion and the Chronic Care Model,” Hospital Quarterly 7, no. 1 (2003): 73-82, www.longwoods.com.

- Keast, “Ontario’s Chronic Disease Prevention and Management Framework.”

- Canada, “The Human Face of Mental Health and Mental Illness in Canada 2006,” Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada (2006), p. 31,www.phac-aspc.gc.ca.

- World Health Organization, “The World Health Report 2001, Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope” (2001), www.who.int.

- Canada, “The Human Face of Mental Health and Mental Illness in Canada 2006,” p. 59.

- Keast, “Ontario’s Chronic Disease Prevention and Management Framework.”

- Ontario, “Making It Happen: Implementation Plan for Mental Health Reform,” Ministry of Health and Long-term Care (Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 1999),www.health.gov.on.ca.

- John Trainor, Ed Pomeroy and Bonnie Pape, A Framework for Support, Third Edition (Canadian Mental Health Association, National Office, 2004), p. 23,www.cmha.ca.

- Public Health Standards Technical Review Committee, “Ontario Public Health Standards” (April 30, 2007), p. 27, www.health.gov.on.ca.

- Public Health Standards Technical Review Committee, “Ontario Public Health Standards,” pp. 28-30.

- Keast, “Ontario’s Chronic Disease Prevention and Management Framework.”

- Ontario Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance and Health Nexus, “Primer to Action: Social Determinants of Health” (May 2008), www.healthnexus.ca.

- Emma Haydon et al., “Chronic Disease in Ontario and Canada: Determinants, Risk Factors and Prevention Priorities” (Ontario Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance and Ontario Public Health Association, March 2006), pp. 47-52,www.ocdpa.on.ca.

- Australia, “Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention for Mental Health,” Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care (Commonwealth of Australia, 2000), p. 18, auseinet.flinders.edu.au.

- World Health Organization, “Prevention of Mental Disorders, Effective Interventions and Policy Options,” (2004), p. 13, www.who.int.

- David P. J. Osborn et al., “Relative Risk of Cardiovascular and Cancer Mortality in People with Severe Mental Illness from the United Kingdom’s General Practice Research Database,” Archives of General Psychiatry 64 (2007): 242-249,archpsyc.ama-assn.org.

- Mythily Subramaniam, Siow-Ann Chong and Elaine Pek, “Diabetes Mellitus and Impaired Glucose Tolerance in Patients with Schizophrenia,” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 48, no. 5 (2003): 345-347, www.cpa-apc.org.

- Mercedes R. Carnethon et al., “Longitudinal Association between Depressive Symptoms and Incident Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Older Adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study,” Archives of Internal Medicine 167 (2007): 802-807,archinte.ama-assn.org.

- Vincent Woo, Stewart B. Harris and Robyn L. Houlden, “Canadian Diabetes Association Position Paper: Antipsychotic Medications and the Associated Risks of Weight Gain and Diabetes,” Canadian Journal of Diabetes 29, no. 2 (2005): 111-112, www.diabetes.ca.

- Tony A. Cohn and Michael J. Sernyak, “Metabolic Monitoring for Patients Treated with Antipsychotic Medications,” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 51, no. 8 (2006): 492-501, www.cpa-apc.org.

- Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance of Canada, “Poverty and Chronic Disease: Recommendations for Action” (April 2008), www.cdpac.ca.

- Stephen Kisely et al., “Inequitable Access for Mentally Ill Patients to Some Medically Necessary Procedures,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 176, no. 6 (2007): 779-784, www.cmaj.ca.

- Kate Lorig et al., “Effect of a Self-Management Program on Patients with Chronic Disease,” Effective Clinical Practice 4, no. 6 (2001): 256-262,www.acponline.org.

- Canadian Mental Health Association, British Columbia Division, “Bounce Back: Reclaim Your Health,” www.cmha.bc.ca.

- Trainor, Pomeroy and Pape, A Framework for Support.

- Anne E. Rhodes, Jennifer Bethell and Susan E. Schultz, “Primary Mental Health Care,” in Primary Care in Ontario: ICES Atlas, ed, L. Jaakkimainen et al. (Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2006), pp. 155-156,www.ices.on.ca.

- Rhodes, Bethell and Schultz, “Primary Mental Health Care,” p. 142.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information, “The Evolving Role of Canada’s Fee-for-Service Family Physicians 1994-2003” (Ottawa: 2006), www.cihi.ca.

- Ontario Guidelines Advisory Committee, “Screening for Depression,” Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and Ontario Medical Association, GAC Summary of the Recommended Guideline, no. 214 (June 2007), www.gacguidelines.ca.

- Harriet L. MacMillan et al., “Screening for Depression in Primary Care: Recommendation Statement from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 172, no. 1 (January 4, 2005): 33-35,www.cmaj.ca.

- Nick Kates and Michele Mach, “Chronic Disease Management for Depression in Primary Care: A Summary of the Current Literature and Implications for Practice,”Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 52, no. 2 (2007): 77-85, publications.cpa-apc.org.

- S. Gilbody, P. Bower, J. Fletcher and D. Richards, “Collaborative Care for Depression: A Cumulative Meta-Analysis and Review of Longer-Term Outcomes,”Archives of Internal Medicine 166, no. 21 (2006): 2314-2321, archinte.ama-assn.org.

- S. Gilbody, P. Whitty, J. Grimshaw and R. Thomas, “Education and Organizational Interventions to Improve the Management of Depression in Primary Care: A Systematic Review,” Journal of the American Medical Association 289, no. 23 (2003): 3145-3151, jama.ama-assn.org.

- David J. Katzelnick et al., “Applying Depression-Specific Change Concepts in a Collaborative Breakthrough Series,” Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 31, no. 7 (2005): 386-396, www.ingentaconnect.com.

- A. Neumeyer-Gromen et al., “Disease Management Programs for Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Medical Care 42, no. 12 (2004): 1211-1221, www.lww-medicalcare.com.

- Pam Lahey, “Opening Doors to Better Care,” Network 23, no. 3 (2008): 4-8,www.ontario.cmha.ca/network.

- Betty Harvey, Diabetes Resource for Mental Health Clinicians, London InterCommunity Health Centre (available from WOTCH Community Mental Health Services, London, Ontario, n.d.).

- Canadian Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health, “Mental Health Literacy: A Review of the Literature” (May 2007), www.camimh.ca.