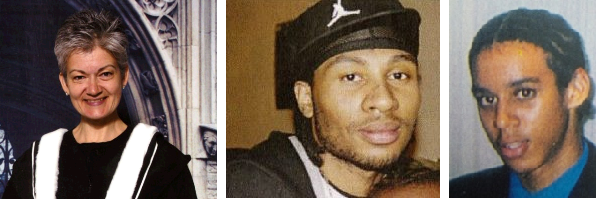

A provincial coroner’s inquest into the deaths of three individuals who were all experiencing a mental health crisis when they were killed by police has begun in Toronto. The deaths of Reyal Jardine-Douglas, Sylvia Klibingaitis and Michael Elgion occurred separately at different times and locations across Toronto over the past three years but their cases are heard together during the 8-week inquest because they were all experiencing mental health issues and holding sharp objects when confronted by police. All officers involved in the three cases were cleared of any charges by the Ontario Special Investigations Unit. The inquest will thus focus on police training and use-of-force guidelines and aim to make recommendations on preventing these types of incidents from occurring in the future.

In the first week of the inquest, the five-member jury heard from policing and mental health experts in order to provide them with sufficient background in current police practices in approaching individuals experiencing mental health issues.

Day 1

The inquest began with an opening statement from Michael Blain, the coroner’s counsel, outlining the circumstance of each death and Dr. David Eden, the presiding coroner, asking the jurors to keep an open mind – stating that an individual should not be defined by his or her mental illness. This was followed by a detailed explanation of use-of-force training and how officers make decisions in the field by John Weiler, the use-of-force co-ordinator at the Ontario Police College.

Day 2

During the second day of the inquest, experts testified that police are not trained to use Tasers or to consider the mental state of the individuals they are confronting with when those individuals are holding a sharp object such as a knife or scissors. Paul Bonner, a defensive tactics instructor with the Ontario Provincial Police, said that police officers are trained to create distance as fast as possible, yell a command like “drop the knife” and draw their firearm when faced with someone holding a sharp object. John Zeyen, an Ontario Police College Taser instructor, says Tasers are rarely used when police officers come into contact with a person armed with a sharp object and that a firearm is the safest option.

Day 3

Dr. Ron Hoffman, an expert in tactical communication with individuals experiencing a mental health crisis, talked about the mental health training new police officer recruits receive. He said that if a person in mental health crisis is not an immediate threat, front-line police should back off, “avoid engaging,” and call for specialized help. He added, however, that there is no hard science on de-escalation and police officers only receive 12 hours of training on mental health issues and how to identify and respond to them.

Day 4

Dr. Mara Goldstein, a psychiatrist from St. Michael’s Hospital emphasized that violence among individuals experiencing mental health issues is rare and difficult to foresee. Dr. Goldstein also spoke about the lack of in-patient psychiatric beds and that the demand for admitting individuals with mental health issues is much greater than the supply of beds.

CMHA Ontario continues to address issues raised during the first week of the inquest by developing policy positions and engaging stakeholders in the following ways:

- In the policy position paper, Conducted Energy Weapons (Tasers), CMHA Ontario holds a firm position on the use of Tasers and has recommended first response alternatives police can use to engage with people experiencing a mental health crisis. CMHA Ontario also believes that more research is needed into the use of Tasers, especially on those living with mental health issues.

- CMHA Ontario worked with the Provincial Human Services and Justice Coordinating Committee (HSJCC) to conduct a critical review of joint police/mental health collaborations in Ontario which identifies innovative practices, their successes and challenges. For example in the Hamilton, Halton, Peel and the Chatham-Kent areas the Crisis Outreach and Support Team (COAST) program brings together multidisciplinary mental health workers (social workers, nurses, etc.) and specially trained, plain clothed police officers that co-respond to mental health crises in the community and link individuals to the appropriate resources. For more information about CMHA Ontario’s work with the Provincial HSJCC, please visit the HSJCC website.

- CMHA Ontario suggests the government introduce evidence-based solutions and expand initiatives such as Mobile Crisis Intervention Teams (MCITs). By partnering mental health professionals with specially-trained officers, MCITs have been successfully implemented in several jurisdictions in Ontario and use a de-escalation approach in instances where police interact with people in a mental health crisis.

The inquest will continue to hear from more than 50 witnesses after which a five-member jury will make recommendations on how to prevent similar deaths from occurring.